I just discovered that the British Library not only put Codex Sinaiticus online, but also built an app that lets us each download our own copy and investigate it on our own.

You can download it from my server here:

https://www.ntgreek.ca/Codex/Codex_Sinaiticus_18-Feb-2013.zip

This is quite incredible, as we get to see with our own eyes one of the two top manuscripts (which we refer to with the symbol א) that we believe gives us the exact words used by the NT authors. This is a manuscript that was created around AD 325, in Alexandria, Egypt, by scribes who were exceptionally well educated, and who were committed to transmitting the words of Scripture with as much accuracy as possible.

Anyway, I will first talk about conjunctions, and then about how to use the Sinaiticus app.

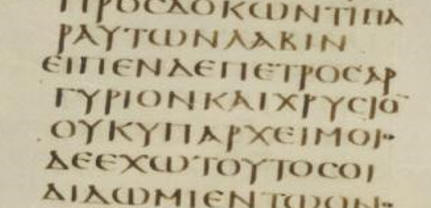

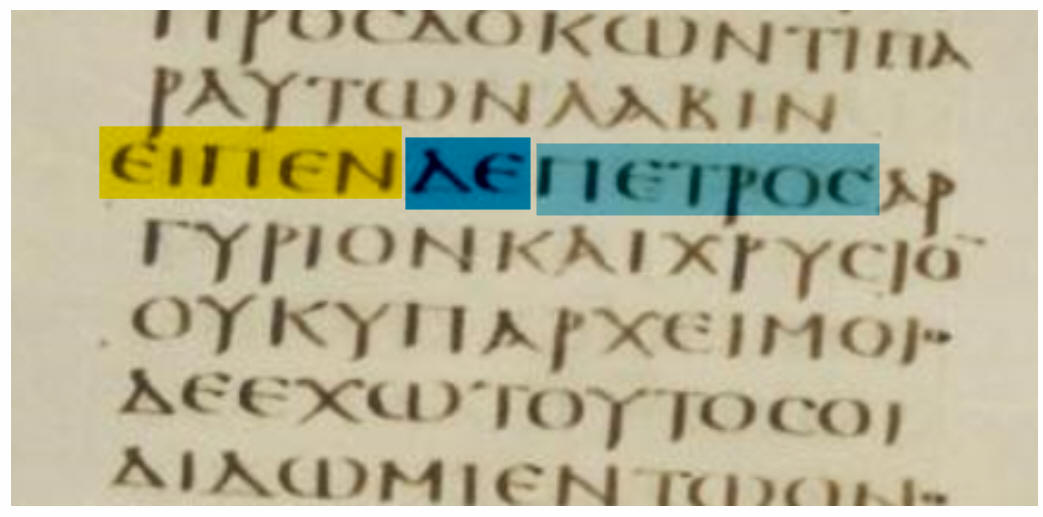

Here you see text, with a slight outdent, an indicator that the scribe thought Luke intended a paragraph break at the beginning of Acts 3:6. Indeed, the copy this scribe was working on may have included that same paragraph break…and there is every chance himself that Luke wrote his original copy of Acts with a paragraph break.

Now, look in your GNT at Acts 3:6, and you will see that it begins with εἶπεν δὲ Πέτρος. If I cast that into upper case Greek letters, and cut out the accents and breathing marks, it would be ΕΙΠΕΝ ΔΕ ΠΕΤΡΟΣ. This is a good example of where δὲ is almost used like a punctuation mark, or even a layout indicator…showing that Luke intended a new paragraph to begin here. And we can ourselves see that there is a bit of a break in the flow of the narrative between Acts 3:5 and 3:6.

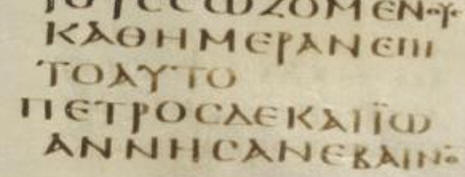

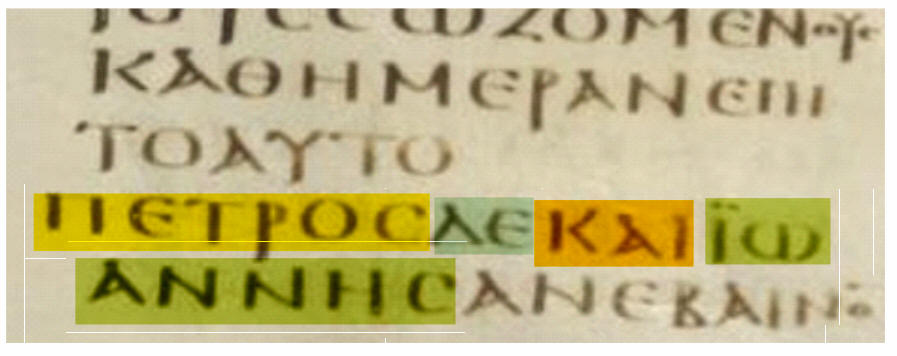

You will of course notice that Peter’s name is spelled with a C at the end rather than a Σ. This is a consistent feature of Sinaiticus, and we can see that in AD 325, in Egypt, a sigma was written like this: C.

If we take a look at Acts 3:1 in Sinaiticus, we will see another δὲ which the scribe has understood to be indicating a break in the narrative. And indeed, in our English Bibles, we begin not just a new paragraph here, but a whole new chapter.

Acts 3:1 reads starts like this in our GNT: Πέτρος δὲ καὶ Ἰωάννης. In upper case letters, this would be: ΠΕΤΡΟΣ ΔΕ ΚΑΙ ΙΩΑΝΝΗΣ. Look closely, and you can see (with C indicating a sigma) these words, with ΙΩΑΝΝΗΣ broken between two lines.

Now, as for using this Sinaiticus app, extract the contents of the Zip file into a folder on your hard drive. There is an EXE file there, but I have scanned it, and it is virus-free. It is OK to double click on.

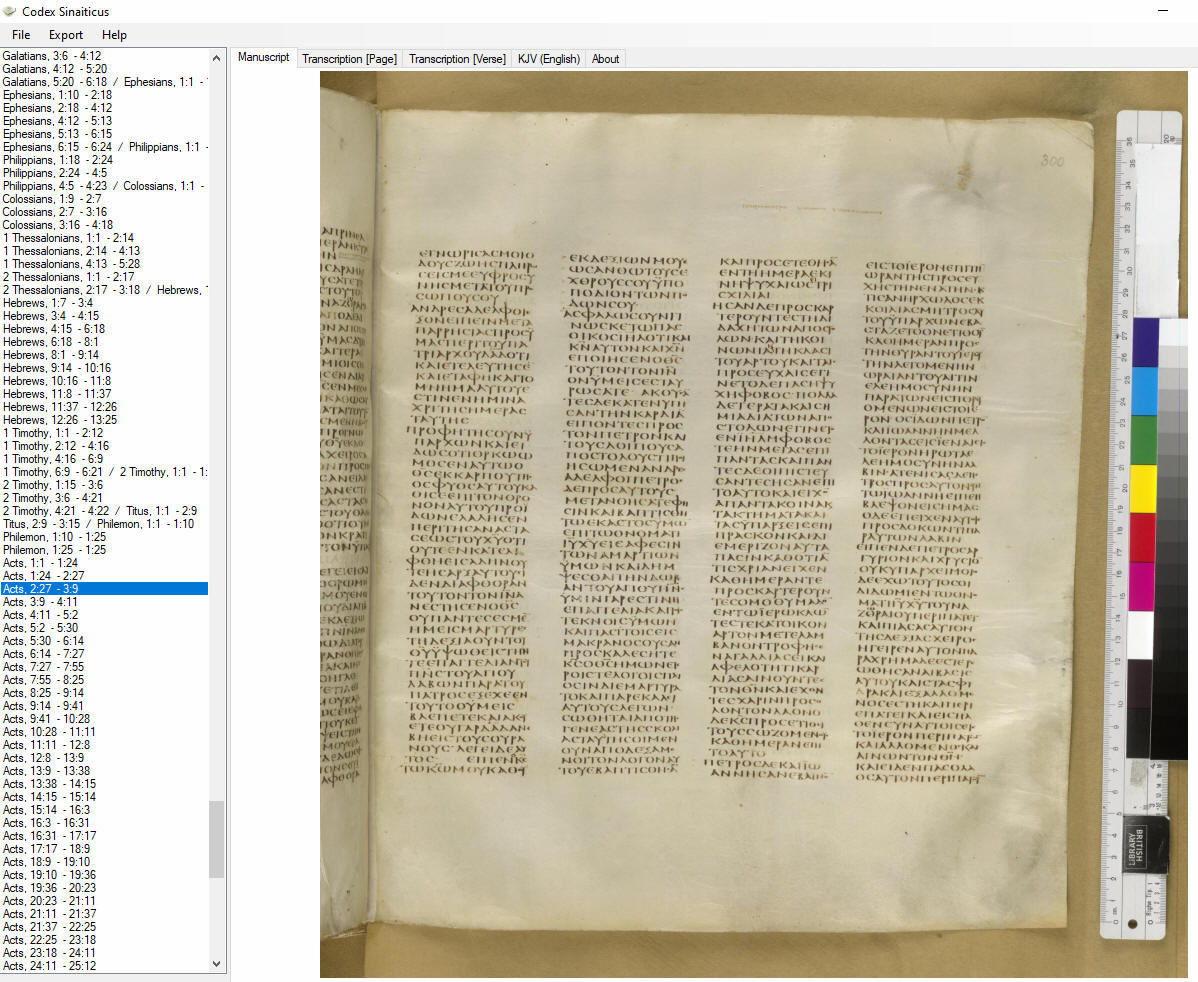

Double click on that EXE (after you have extracted it from the Zip file), and it will open an interface that looks like this:

(This app works like a charm on a Windows computer. It will not work on a Mac. If you have a Mac, you will have to go to:

https://codexsinaiticus.org/en/manuscript.aspx?book=51&chapter=3&lid=en&side=r&zoomSlider=0

…and puzzle out how to use it.)

The table of contents on the left margin indicates the verse range that appears on every page.

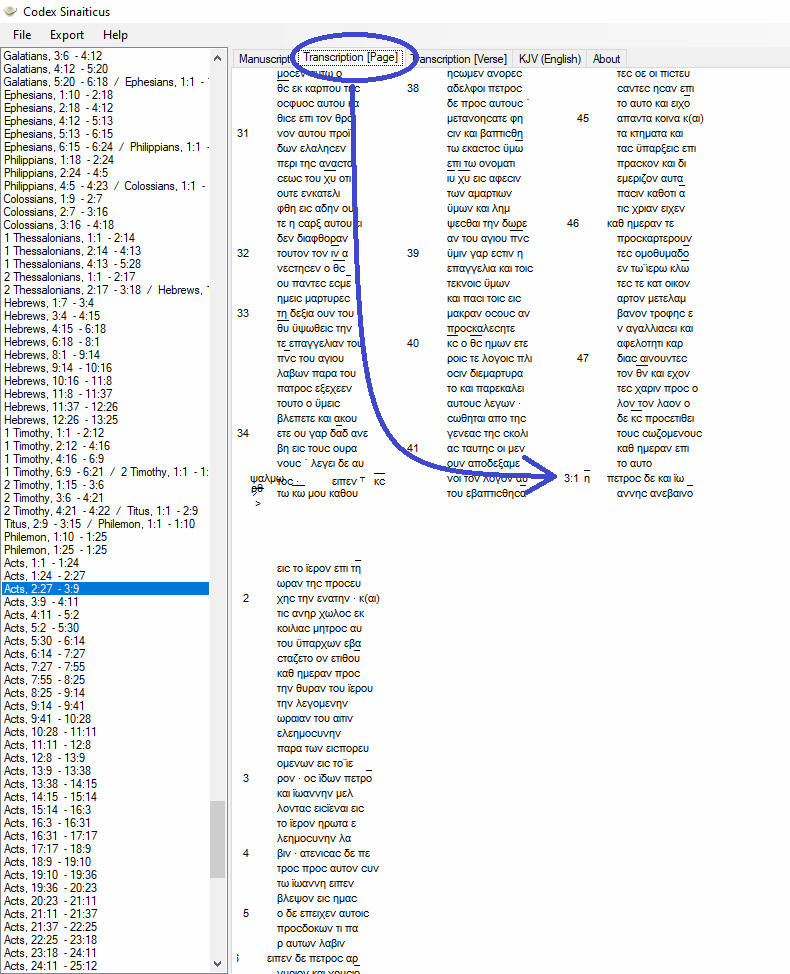

You see that, and you say, “But how can I find a particular verse????” Click on the “Transcription (Page)” tab at the top. It will show you where to look for every verse.

There are four columns of text on every page of the MS, and this transcription page shows you those 4 columns. In this case, once I see that Acts 3:1 starts at the bottom of column 3, two lines up from the bottom, it is easy to go back to the “Manuscript” page and view that verse.

To make it bigger, on your Windows computer, click once on the image of the MS page, anywhere on that page, and it will open that page up in an image-viewer on your computer. From here you can hold down the <ctrl> key and roll your mousewheel, and you can zoom in on the image.

I find this pretty easy to use…much easier than the online version of this “Sinaiticus application”.

What you may choose to do, whenever you get bored, is to open the Sinaiticus app on your computer, and practice reading the Bible with no word breaks, and in all-upper-case characters (with C instead of Σ, and some abbreviations at the end of lines).

For decades, I have heard Canadian preachers talk about “the original Greek”. Well, this is as close to being THE original Greek as it is possible for us to get.

We really have no idea how long Luke’s original copy of Acts existed. If it was written on parchment (the leather from sheep or goats), then it could have lasted for a century or more.

After all, Codex Sinaiticus itself, written on parchment, has lasted for 1,700 years!

This could have potentially been a copy made from Luke’s original (possible, but maybe not too likely), or a copy-of-a-copy of Luke’s original.

In any case א (along with B, called Code Vaticanus, possibly also made in Alexandria, possibly even in the same copy shop [called a “scriptorium”]) goes back far into history, and for the last 150 years, scholars have thought it probably is as close to the actual original wording as is possible to get.

Whenever I see textual variants in the GNT, and I look into the various manuscripts, if א and B agree with each other, I find it pretty persuasive that they capture the original wording of the apostles.

The SBLGNT does not refer directly to old manuscripts, but to 19th c. and 20th c. editions of the Greek NT, which themselves look back to ancient manuscripts.

For a chance to look at the actual manuscript evidence, your best bet is to go to www.NetBible.org. For instance, you will find a text-critical (i.e. textual analysis) note for Matthew 2:18, and that the NetBible translators went with the wording from א and B.

Since pretty well everybody likes א and B, you will find that the virtually all of the modern versions base their translations on the same reading of Matt. 2:18.

If you are like me, and you someday get hooked on analyzing manuscripts, then you will do what I did, and purchase this commentary:

It goes into quite a bit more detail than the NetBible notes, and covers a greater number of variants. In each case, Metzger explains the basis upon which the GNT editors made their decision.

This is also available in India from:

Now, you don’t NEED to purchase this commentary. At the end of the day, you can trust the GNT you purchased (or the SBLGNT online), and devote more of your time to translating, and then deciding how to live out what Jesus wants of us. THAT is the really practical thing to do. Buying Metzger’s textual commentary is more like a hobby, if you find yourself particularly interested in textual variants.

After reflecting on the appearance of upper case Sigmas as

C in Codex Sinaiticus, I went to Wikipedia to see what I could learn.

We today typically represent an upper case Sigma as Σ. It turns out that this

was the way that the character was written during the “Classical Greek” period,

from the from 500 to 300 BC. Σ was an ideal shape if you were cutting it into a

tombstone or other such material.

With the “Koine Greek” period that started with Alexander the Great, people

began writing Σ as C, as it was an easier to write the character with pen and

paper (or rather, papyrus or parchment).

C is called a “lunate Sigma”—taken from the name “lunar”, based on the shape of

the crescent moon.

If we think of “Ancient Greek” as encompassing a thousand-year history from

Homer to Herodotus and Plato, on down to Codex Sinaiticus, then the reality is

that there was a slight shift in how the alphabet was written during that

period…and we have to choose from one or the other form of Sigma as our

“official” form today. Scholars decided during the Renaissance that we would all

use the Σ rather than the C.

This is fine, and makes it easy to read ancient stone tablets (such as the

bottommost language of the

Rosetta

Stone—be sure to use [Ctrl] and your mousewheel to zoom in enough to read the bottom section). We just have to switch mental gears a bit when we go to read

Sinaiticus.